How to Build An ARM64 Docker Image Running Chrome Headless Shell

This is a story of how I built chromedp for ARM64 and then used Pulumi to automate the entire build process on Google Cloud Platform. Now before we dive into this, let’s answer a few questions you may have:

What is chromedp and why use it?

Chromedp is an open source tool kit that allows developers to write code and automate the Google Chrome browser. Think of it like writing a bot to make Google Chrome do things. For example, let’s say you wanted to get a screenshot of the Reddit front page emailed to you daily. Instead of manually doing this, you can automate it using chromedp.

One important feature of chromedp is that it is a Golang module. So basically, the program that I described above, is written in Go and would have the following structure:

// Command screenshot is a chromedp example demonstrating how to take a

// screenshot of a specific element and of the entire browser viewport.

package main

import (

"context"

"log"

"os"

"github.com/chromedp/chromedp"

)

func main() {

// create context

ctx, cancel := chromedp.NewContext(

context.Background(),

)

defer cancel()

// capture entire browser viewport, returning png with quality=90

if err := chromedp.Run(ctx, fullScreenshot(`https://reddit.com/`, 90, &buf)); err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

if err := os.WriteFile("fullScreenshot.png", buf, 0o644); err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

log.Printf("wrote fullScreenshot.png")

}

// fullScreenshot takes a screenshot of the entire browser viewport.

//

// Note: chromedp.FullScreenshot overrides the device's emulation settings. Use

// device.Reset to reset the emulation and viewport settings.

func fullScreenshot(urlstr string, quality int, res *[]byte) chromedp.Tasks {

return chromedp.Tasks{

chromedp.Navigate(urlstr),

chromedp.FullScreenshot(res, quality),

}

If you prefer to use JavaScript, I recommend you check out Puppeteer from Google. It uses Node.js and offers the same functionality while allowing you to write your code in JavaScript. I am, however, a huge fan of Go and so for the rest of this article, my focus will be solely on that.

How does it work?

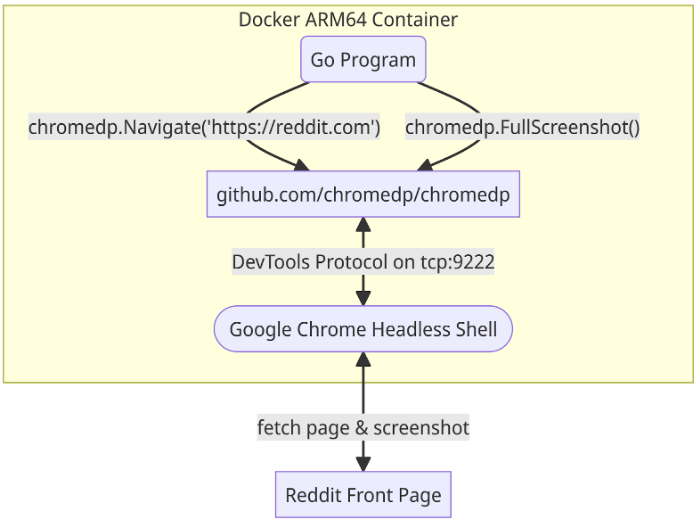

Fig 1.1 – How your Go program calls chromedp and Chrome Headless Shell

The more eagle-eyed of you would have noticed that there is essentially no mention or configuration of a browser. The reason is chromedp requires a prerequisite of having Google Chrome installed on your machine. It will look in the system’s path and other possible locations where Google Chrome would be installed.

If you would like to see this list, have a look at the source code here: [https://github.com/chromedp/chromedp/blob/f468fe96718b2edb1c28d22c351cd7c96834b3a4/allocate.go#LL349C15-L349C15]

chromedp works by launching the Google Chrome browser and using the Chrome DevTools Protocol (CDP) to control it. From there, chromedp.Navigate(urlstr) will make the browser navigate and load the URL string (urlstr). Then, chromedp.FullScreenshot(res, quality) will take the screenshot (Fig 1.1).

There are certainly many other things chromedp can do, including filling forms, clicking specific buttons, and interacting with the HTML DOM. But that is, in a nutshell, how chromedp is designed. You launch the browser, then leverage the chromedp API to drive that browser and perform different things with it.

So why the whole ceremony of building for ARM64?

In short, I want to test it on my Mac. The longer version of the story is this: chromedp allows you to make use of this “Headless” Google Chrome browser. “Headless” means that the browser runs, but you won’t see the actual browser window. The premise is that if a program is driving the browser, unlike a human, it doesn’t always require a visible browser window. To settle this, the authors of chromedp have built a Docker image that includes the Google Chrome Headless Shell. A build of Chrome without the browser window for humans. This is a very neat way to use chromedp.

Because it runs in Docker, I do not need to pollute my MacBook by installing Google Chrome on it. When it comes to building, testing, and running software, I frequently use Docker. I like how it provides isolation and determinism in my build environments. I may write a post about that sometime in the future. For now, I want to test headless Chrome in a Docker image. As a result, I am now challenged by the fact that My Mac is equipped with an M2 processor, which is ARM64, making it incompatible with the chromedp version of the Docker Image. Therefore I set about building an ARM64 Docker image specifically for me to use and test.

Now you may be tempted to tell me the myriad of ways I can solve my problem, including emulating x86-64 to run the image, and you would be right. There’s more than one way to solve this problem, but I opted for this approach.

Building Chrome on Linux for x86_64 first

The team at chromedp have released the source code on how they build their headless Docker image. So let’s start there first.

You can find the repo here: https://github.com/chromedp/docker-headless-shell. I am specifically interested in this file: build-headless-shell.sh because it has the code automation required to build Google Chrome’s headless browser. If you were to follow the steps in how to build Google Chrome from source, it would more or less match what is going on in this script. This is what I did first instead of using the build script. I followed the given instructions and manually built Chrome on my Linux laptop.

My laptop is powered by an AMD Ryzen processor with 8 cores and equipped with 64GB of RAM. On average, it took approximately 2 hours to complete the build process. I don’t really know why but for one, the download speed to get all the Chrome source was slow and then of course, the build itself took a while, even on a machine that I consider decently sized. The end result, however, was that I was able to build x86_64 Chrome from the source which gave me some confidence to then try and build it for ARM64. So after a bit of online searching and reading this doc, I proceeded to build Chrome for ARM64.

Differences in the builds

Before we talk about the differences, I want to point out one weird quirk in building Chrome. It is not possible to build an ARM64 version of Chrome on ARM64 Linux. You had to explicitly cross-compile it on a Linux x86_64 box. I found that a touch bizarre, but I guess it makes sense as the build process for x86_64 was probably streamlined enough where simple cross-compilation was all that was required. I learned this the hard way trying to build inside a Linux ARM64 container.

In any case, the cross compile itself was fairly straightforward. Here are the main set of differences:

- Installing the build dependencies – For this, the usual command is to run install-build-deps.sh with no arguments. For ARM64, however, you have to specify the flag as follows: install-build-deps.sh –arm. Additionally, you can add further flags as needed.. In my case, since I am not building Native Client (NaCl), I specify that also.

- When using gn, you will first have to specify some arguments to generate the build files. In this set of arguments, it is essential to add target_cpu=“arm64” so that the relevant build files are generated.

- Before running gn gen,an ARM64 sysroot needs to be installed. A sysroot is basically the most basic set of libraries, and header files to have a minimal version of an operating system for that specific architecture. Therefore, in our case, we need to install the sysroot for Linux ARM64 by running: ./build/linux/sysroot_scripts/install-sysroot.py –arch=arm64

That’s pretty much it. Overall, it is fairly simple as all the relevant functionality exists for you to cross-compile effectively.

With this, I was able to build a Chrome version that was capable of running on ARM64, I simply copied it over to my Mac and tested it out. It worked just fine. The last step was undoubtedly to build the Docker image, which I did. One thing to keep in mind is that I did not want to build the version of Chrome with the browser window for human use but the headless version – which, luckily, there exists a way of doing. To accomplish it, you need to specify that during the gn argument creation portion of the build.

Automating the build process

With those changes implemented and a successful build for ARM64 done, I made the relevant changes in the automated build scripts and then tested those. You can find the final source code on how to build Headless Chrome for ARM64 in our Github repo here:

https://github.com/madison-tech/docker-headless-shell/tree/arm64

Make sure that you are on the ARM64 branch as the master branch still tracks the x86_64 version of the build.

Now that I had the automated build script working, I moved on to solve two things:

- How do I build this on demand, but build it fast?

- How should I have it so that other Madison team members can use it?

Building Chrome is obviously not something I would be doing regularly. The proper approach is to have the first download of the source code, and for subsequent builds, you only sync the changes from the Chrome repo. But that meant I had to always track the source on my laptop and keep it on there. It would take up space and I may end up tinkering with the source code and leave it in an unpredictable state. Hence, I decided to make it an on-demand build process.

Enter Google Cloud Platform

I know that GCP has a sweet 30 core C2 instance that is optimised for compute only. It comes with 120GB of RAM but I don’t need such a substantial amount.. My goal was to see how quickly I could cut down my build time by using this machine. It is not at all a cheap machine, but if I can provision, build quickly, and then terminate the instance, I could probably get it done with a few dollars each time I needed to build Chrome. So, the problem to solve now was fairly clear.

Hello Pulumi

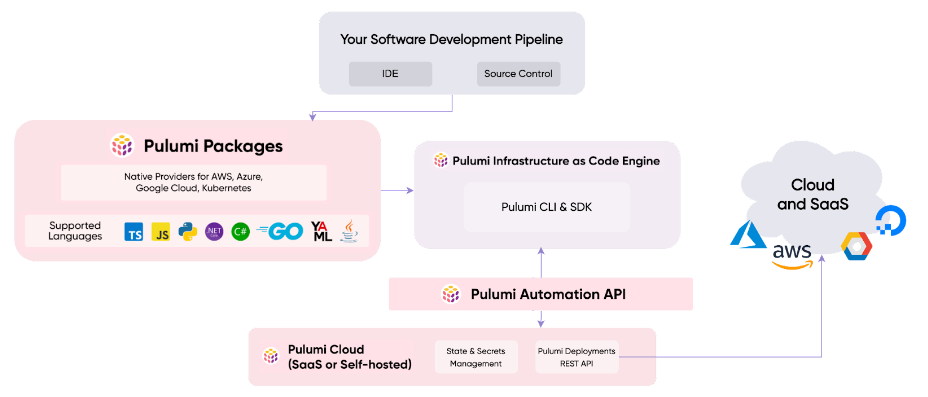

Fig 1.2 – The Pulumi Infrastructure as Code Overview

I turned to Pulumi to help with the task I have to provision, build, and tear down this resource on GCP. We use Pulumi for both internal and client projects for automating and establishing deterministic cloud infrastructure setups. It makes us 10x more efficient because our Developers can execute cloud infrastructure setups without relying too heavily on our DevOps team. Pulumi expresses infrastructure as code and allows you to provision machines in Go, Python, Node.js, Typescript, Javascript, Java, or .NET. Since it’s in a language our developers are familiar with, it becomes much easier for them to participate in the DevOps component of projects (Fig 1.2).

I wrote a very basic Pulumi program in Go to solve the problem. I had Pulumi spin up a C2-standard-30 VM instance, used a startup script to fetch the automated Chrome build code and run it. After I had copied it, I could run a simple command: pulumi –destroy to get rid of the VM I had provisioned.

Here is the code that I use to setup the build environment: https://github.com/madison-tech/buildchrome

You will also likely notice that I set up Tailscale on my VM instance so that I can easily connect to it via SSH. I did this because I have some additional features that I want to add to my code. Basically, I intend to set up a web server on my laptop and have the build VM send a GET request to it. This way, I can automatically perform some other steps of copying the build off the VM, and finally running the destroy script to clean up the cloud infrastructure resources. When setting up VMs on the cloud, I use Tailscale to connect to it rather than leaving any initial ports open when provisioning (by default, SSH will be open on the VM). This ensures the VM is inaccessible from the outside until it is ready to go into production. Tailscale is on the very top of my list of favourite tools, year after year after year.

Closing Thoughts

This post should give you a small glimpse into how we view DevOps at Madison. As a small company, we have to be as efficient as possible with our team. Pulumi helps us achieve this very well which offers the following advantages::

- We can easily have repeatable tasks setup so that any one of our team members can use it.

- It reduces mistakes because it is written once and is automatic.

- It helps us build deterministic cloud infrastructure every time.

On the topic of being efficient, we also ensure our QA team has time to do the more involved manual testing. Therefore, we use tools like chromedp or Puppeteer to build out automated QA tasks that we can run as part of a build pipeline.

Hope you guys enjoyed this post. Stay tuned for more stories and content on topics of automation and how you can do more with less. Bye for now!

About the Author

Sheran Gunasekera is a security researcher and software developer. He is co-founder and Director of Research for Madison Technologies, a product development company in Singapore, where he advises the in-house engineering team in both personal computer and mobile device security. Sheran’s foray into mobile security began in 2009 when he started with BlackBerry security research. Since then, he has been in leadership roles in both engineering and security at several start-ups in Asia including GOJEK, the on-demand multi-service app that is now publicly listed.